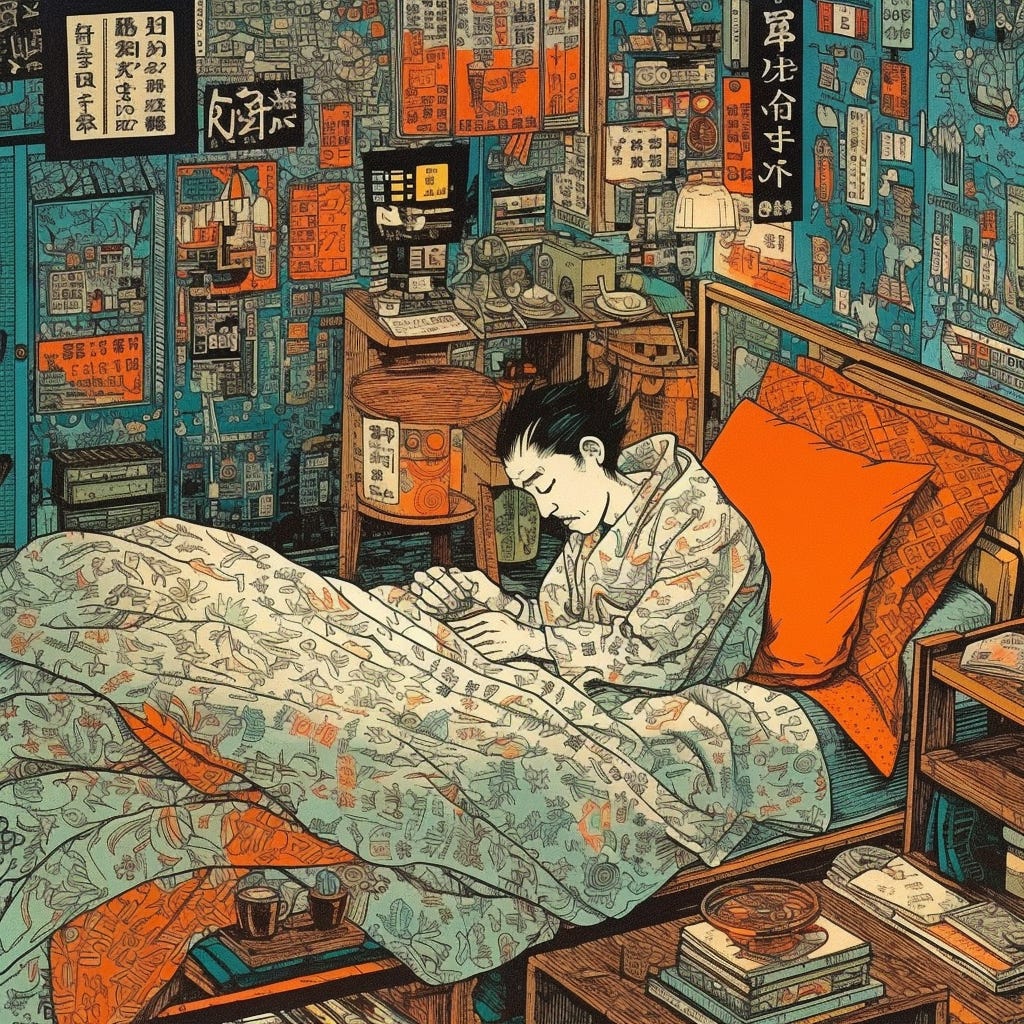

Why You Should Study Before Going to Sleep

What are the effects of sleep on memory formation?

Anecdotally, it has long been known that learning before going to sleep has a positive effect on memory. But what does the scientific research say?

In this post, I’ll review a few articles and scientific studies that address this topic.

An Old Idea

The benefits of learning before going to sleep have been known for thousands of years, as pointed out by the 1st-century Roman rhetorician Quintilian:

It is a curious fact, of which the reason is not obvious, that the interval of a single night will greatly increase the strength of the memory, whether this be due to the fact that it has rested from the labour, the fatigue of which constituted the obstacle to success, or whether it be that the power of recollection, which is the most important element of memory, undergoes a process of ripening and maturing during the time which intervenes.

Quintilian

But let’s take a look at some more recent research.

The Memory Function of Sleep

This review article from 2010 covers a number of different studies on sleep and memory function. It summarizes a number of helpful findings:

Numerous studies have confirmed the beneficial effect of sleep on declarative and procedural memory in various tasks, with practically no evidence for the opposite effect (sleep promoting forgetting.)

Compared with a wake interval of equal length, a period of post-learning sleep enhances retention of declarative information and improves performance in procedural skills.

Significant sleep benefits on memory are observed after an 8-hour night of sleep, but also after shorter naps of 1–2 hours and even an ultra-short nap of 6 minutes can improve memory retention.

However, longer sleep durations yield greater improvements, particularly for procedural memories.

The optimal amount of sleep needed to benefit memory and how this might generalize across species showing different sleep durations is unclear at present.

Naps Also Work

An article by the UPenn School of Medicine explains the impact of sleep on memory in more accessible terms. One section references this paper and was particularly relevant:

In one study, a group of 44 participants underwent two rigorous sessions of learning, once at noon and again at 6:00 PM. Half of the group was allowed to nap between sessions, while the other half took part in standard activities. The researchers found that the group that napped between learning sessions learned just as easily at 6:00 PM as they did at noon. The group that didn’t nap, however, experienced a significant decrease in learning ability.

Another study, conducted at the University of Notre Dame, showed that going to sleep shortly after learning new material is most beneficial for recall:

[Scientists] studied 207 students who habitually slept for at least six hours per night. Participants were randomly assigned to study declarative, semantically related or unrelated word pairs at 9 a.m. or 9 p.m., and returned for testing 30 minutes, 12 hours or 24 hours later.

Declarative memory refers to the ability to consciously remember facts and events, and can be broken down into episodic memory (memory for events) and semantic memory (memory for facts about the world). People routinely use both types of memory every day — recalling where we parked today or learning how a colleague prefers to be addressed.At the 12-hour retest, memory overall was superior following a night of sleep compared to a day of wakefulness. However, this performance difference was a result of a pronounced deterioration in memory for unrelated word pairs; there was no sleep-wake difference for related word pairs. At the 24-hour retest, with all subjects having received both a full night of sleep and a full day of wakefulness, subjects’ memories were superior when sleep occurred shortly after learning, rather than following a full day of wakefulness.

Faces, Not Just Facts

The effect doesn’t only apply to words, either. A similar study conducted at Brigham and Women’s Hospital tested memory recall by using faces:

Fourteen participants were tested twice. Each time, they were presented 20 photos of faces with a corresponding name. Twelve hours later, they were shown each face twice, once with the correct and once with an incorrect name, and asked if each face-name combination was correct and to rate their confidence. In one condition the 12-hour interval between presentation and recall included an 8-hour nighttime sleep opportunity (“Sleep”), while in the other condition they remained awake (“Wake”).

The result?

There were more correct and highly confident correct responses when the interval between presentation and recall included a sleep opportunity, although improvement between the “Wake” and “Sleep” conditions was not related to duration of sleep or any sleep stage.

Future Research

I had other questions, but wasn’t able to find research studies addressing them. For example, are multiple naps adding up to 8 hours superior to a single 8 hour sleeping block? Is there a daily limit to the amount of learning that can be processed while sleeping?

In a more actionable sense, I also wondered if a succession of sleep-learn-sleep-learn periods would be the optimal form of learning, better than simply learning and then going to bed.

I’m imagining an intensive training program where you learn for 2 hours then sleep for 1 hour – and then repeat this process over the course of a day, week, or month. It would require some complex logistics and the ability to fall asleep quickly, but if the learning benefits are significantly better than the “standard” way of studying, it’s worth investigating.